Aaron Haines

Aaron Haines

Investigators: Aaron Haines, Julie Zeyzus, Nicole Notarianni, John Chenger and Bryan Butler

Bat species benefit human societies and biological systems by being indicators of ecosystem health and providing biological control over problem insect species. A number of studies have used bats as indicators of ecosystem health with bat activity positively correlated to areas with higher water quality.

Currently, there are a number of bat species in Pennsylvania that are species of conservation concern. Ten years ago, the Little brown bat, Tricolored bat and Northern long-eared bat were common and widespread species in Pennsylvania. In the last decade, populations of these bat species have declined dramatically with the onset and spread of the fungus that causes the white-nose syndrome (WNS) disease (Pseudogymnoascus destructans). Population sizes for many bat species were reduced, some up to 98%, causing regional extinctions of populations. The conservation of remnant bat colonies is an increasing priority for research throughout Pennsylvania and North America.

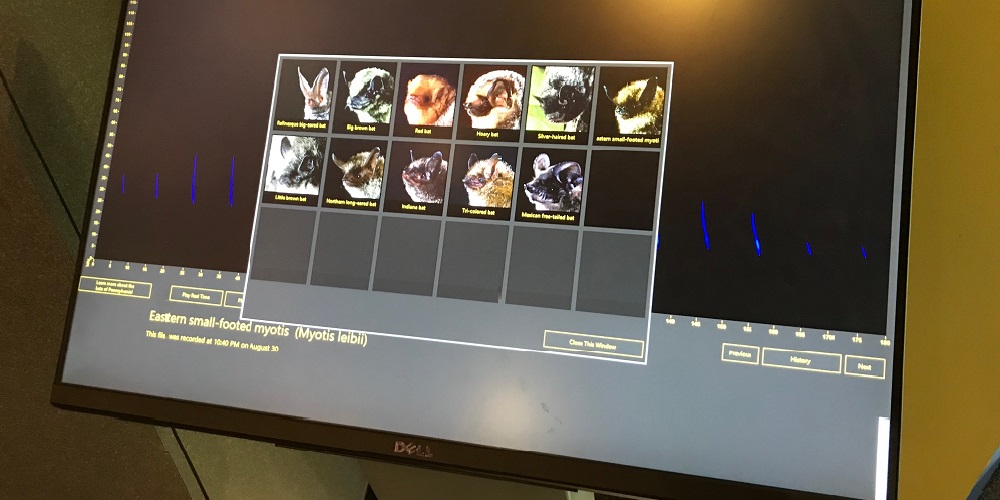

The goal for this project was to inventory insectivorous bat activity through the deployment of remote acoustic devices along the Kittatinny Ridge. This included establishing a remote bat kiosk recording device at the Hawk Mountain Nature Center that allowed the public to view local bat activity via recordings of bat vocalizations. Using these remote acoustic recording devices, we assessed bat species activity along the Kittatinny Ridge.

Remote monitoring efforts to identify bat species activity based on their vocalizations can help reduce cost of labor in determining areas that are of importance to wild bat conservation. A bat’s ability to effectively and efficiently catch prey on the wing is due to their ability to echolocate. These signals can be detected by ultrasonic microphones which convert the ultrasound to audible sounds and stores time-stamped call data on an external drive. In recent years, the sophistication of new bat detector technology, as well as the commercial availability of call analysis programs, have made acoustic monitoring a viable option for data collection to be used in future bat management decisions.

Five temporary acoustic monitoring sites were placed in natural areas dispersed along the Kittatinny Ridge: Cowans Gap State Park, Swatara State Park, Boyd Big Tree Preserve Conservation Area, Lehigh Gap Nature Center and Jacobsburg Environmental Education Center.

Bat surveys were conducted using D500X ultrasound bat recording units (Pettersson Elektronik AB, Uppsala, Sweden) to remotely survey bat activity in each of the 5 natural areas. Recording devices were placed in areas most suitable for bat ultrasound detection free from obstruction: (a) forest-canopy openings, (b) near water sources, (c) wooded fence lines adjacent to large openings, (d) blocks of recently logged forest where potential roost trees remain, (e) road and/or stream corridors with open tree canopies, and (f) woodland edges. We also established a remote bat recording device kiosk at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary.

Each of the 6 natural areas was surveyed for bat activity for at least 14-31 nights during the summer of 2018 and the spring and summer of 2019. We recorded the greatest number of identified bat calls per survey night at Boyd Big Tree Preserve, this survey location was by far the most active site for bats. Based on bat ultrasound recordings, we detected activity for a total of 9 different bat species along the Kitattinny Ridge of Pennsylvania. Since 1987, 11 bat species have been found to reside within the entire Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the only two species we did not detect included the Indiana bat and the Seminole bat. At Cowans Gap State Park, Swatara State Park and Lehigh Gap Nature Center, we identified calls for a Myotis species of bat, one of which could have been an Indiana bat. We recommend expanding survey efforts in each natural area to include different habitat sites (e.g., interior forest, forest edge) and identifying other natural areas along the Kittatinny Ridge to survey. See data collected here.

For bats roosting along the Kittatinny Ridge of Pennsylvania, forest management that includes protecting important roost trees in mature forests juxtaposed to freshwater resources such as ponds, marshes, stream pools and rivers that provide open flight paths for foraging bats is extremely important. For bats that overwinter in Pennsylvania, protection of hibernacula is essential. This would include mitigating activities that would continue the spread of the WNS fungus, establishing bat friendly gates in front of caves or mines and conducting public outreach to the caving (or spelunking) community.

Acknowledgements and Contact Information

We thank the following individuals for their help and support during this project: Jeanne Ortiz, Dan Kunkle, Diane Hustic, Heather Rossell, Debee Ordway, Carter Farmer, Nick Szewczak, Laurie Goodrich, Mary Linkevich, Todd Bauman, Jack Hill, Chris Houck, Chad Schwartz, Robert Neitz, Jason Baker, Emilee Boyer, Eileen Haines, George Barner and Mary-Therese Grob. We especially want to thank Kenneth Dunkelberger for setting up the remote download capability of the bat acoustic kiosk at Hawk Mountain.

This project was financed by Bat Conservation and Management and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) through DCNR’s Environmental Stewardship Fund administered by the Bureau of Recreation and Conservation. The DCNR grant is administered by the Kittatinny Coalition through Audubon Pennsylvania.